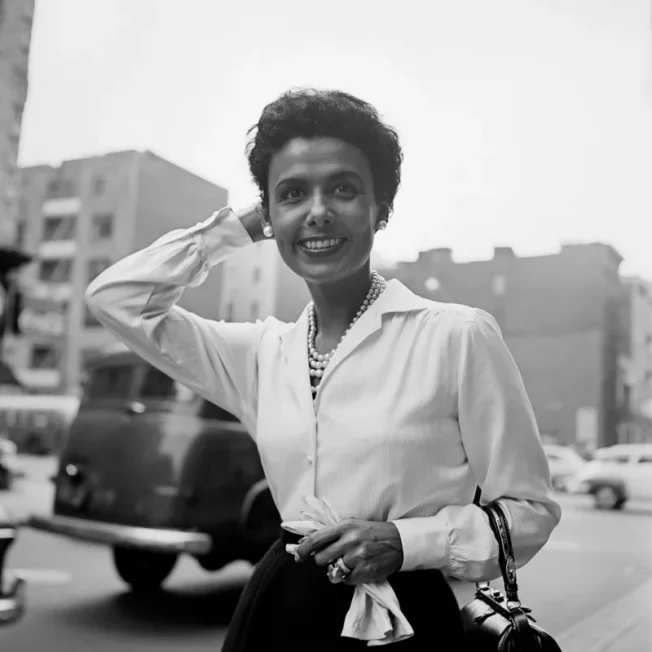

Broadway has paid homage to a legendary dancer and Civil Rights activist: Lena Horne. On November 1, the Brooks Atkinson Theatre was officially unveiled under a new name, the Lena Horne Theatre, marking the first time a Broadway theater was named after a Black woman. The momentous occasion reinvigorated the memory of Horne, who passed away on May 9, 2010, at age 92.

With Horne’s legacy honored with the historic gesture, let’s take a trip into the past to learn more about the performer who ultimately broke ground for Black performers for generations to come.

Lena Horne’s early life

On June 30, 1917, Lena Mary Calhoun Horne was born in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn to father Edwin Fletcher “Teddy” Horne Jr. and mother Edna Louise Scottron, an actress in a black theater troupe. While she was raised mainly by her grandparents, Cora Calhoun and Edwin Horne, she moved to Georgia when she was five-years-old. As a child, she traveled with her mother, and for two years, between 1927 and 1929, she lived with her uncle in Fort Valley, Georgia, before moving to Atlanta briefly with her mother. It wasn’t until she was 12-years-old that she returned to New York.

Instead of finishing school, Horne dropped out when she was 16 and began performing at the Cotton Club in Harlem, New York. Her Broadway debut came in 1934 when she appeared in the production of “Dance With Your Gods,” followed by her next move, which was joining Noble Sissle and His Orchestra as a singer. By 1939, Horne appeared in another Broadway musical, “Blackbirds of 1939,” before joining the white swing band, the Charlie Barnet Orchestra. However, she ultimately left the band and the tour due to racial prejudice, with Horne unable to stay at the venues where the band performed.

But that was only the start for Horne.

The height of her career

For seven decades, Horne’s career flourished in every talent imaginable as an actress, dancer, and singer. She eventually moved to Hollywood and began acting in small roles in films. Though she, like many Black actors, struggled at the helm of her career to receive serious roles due to the racial barrier in the industry, by the mid-1940s, Horne was one of the top-paid Black actors in the United States. She starred in films including “Deed I Do” and “As Long as I Live,” which have become classics over the years.

Unfortunately, Horne’s career as an actress was halted during the anti-Communist movement, with the performer being branded a sympathizer due to her activism when it came to Civil Rights and some of her close friendships. Blacklisted from films and television, Horne turned to music and began performing in nightclubs and making her recordings, including the 1957 live album “Lena Horne at the Waldorf Astoria.” And by the 1960s, Horne was back on top.

Horne’s activism remained part of her ethos as a performer. She joined the March on Washington and performed at rallies across the country for the National Council for Negro Women. However, Horne stepped back from her career in the 1970s following the death of her son, Edwin Jones, in 1970 and her husband, Lennie Hayton, in 1971. Her comeback would not come until 1981 when she put on a one-person show on Broadway, “Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music,” which ran for 14 months.

The Lena Horne Theatre

The name change for the Brooks Atkinson Theatre stemmed from an agreement between Broadway’s three major landlords and Black Theater United and was originally slated for June 2022. Each landlord agreed to rename at least one of the theaters after a Black artist. Earlier this year, the Cort Theatre was renamed the James Earl Jones Theatre, and the Virginia Theatre was renamed the August Wilson Theatre in 2005.

“On February 13, 1939, Brooks Atkinson wrote a review of the musical Blackbirds of 1939 for the New York Times. His review was generally unfavorable except for the mention of a radiantly beautiful girl, Lena Horne, who will be a winner once she has proper direction,'” Lena Horne’s daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, and the Horne family shared in a statement. “The proper direction came from within Lena herself. She sought an artistic education and a political education. She sought her own voice, found it, and then fought for the right that was always denied her – the right to tell her own story… We’re grateful to the Nederlander Organization for rechristening this space to the Lena Horne Theater. We hope artists and audiences alike will tell their own stories here.”